THE SHELL COLLECTOR

Q & A | Further Reading

Q: Often, your work features natural phenomena or wonders of science. How do you balance your research into or knowledge of the natural world, with the human characters and relationships that are at the heart of any powerful story? Take, for instance, the title story, "The Shell Collector." Which came first: the deadly cone snail, or the character of the blind collector? How did the two find each other?

A: During a visit to Ohio I found an old steel tennis ball can in a closet at my parents' house, and when I pulled off the cap, this strange, crazily familiar smell rose: the smell of dead snails. Inside the can were hundreds of shells that I had collected on trips to Florida with my family during my childhood. Finding them started firing all these large-scale emotions & memories—stuff I hadn't thought about in a long time.

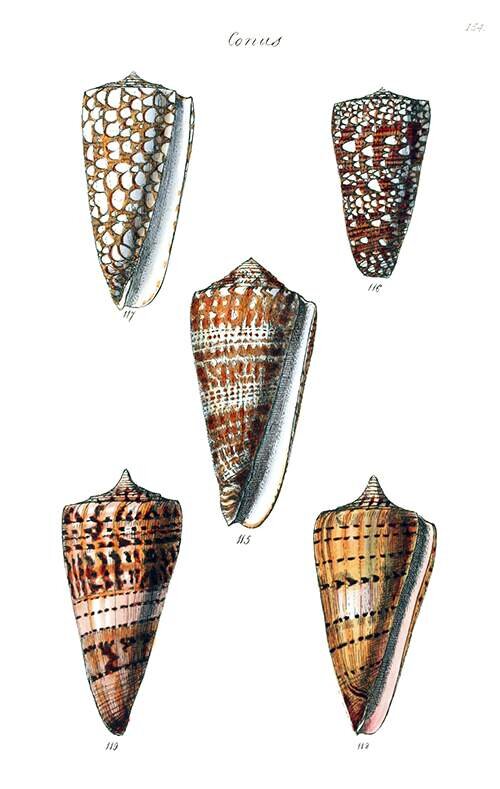

When I was trying to figure out how to write 'The Shell Collector,' I'd sit at my desk and make notes and rolls those old shells between my fingers and look through my journals from when I was in Lamu and read things like papers about cone venom. So the cone snail came first, but with it came memories about being in a very foreign place and littoral zones and moonrises and getting stung by jellyfish and seeing a big, orange moonrise from a treeless island in the Indian Ocean. And the more I read about shells and the formation of them, the more I think the protagonist of “The Shell Collector” coalesced as an amalgam of memory and research and imagination, with the tactile pleasure of holding shells and the associations they fired in me. In my research I read about Geerat Vermeij, a real-life sightless malacologist who has made all sorts of contributions to his field, and learning about Dr. Vermeij gave me permission, I think, to make my character sightless. But research as it might be understood in other disciplines—looking for information—isn't quite I do. I'm looking for interesting things, sure, but I'm really looking for detail, imagery I fall in love, scraps of people I can build into made-up people, the way palm trees shine in the wind, etc. When I’m working well, when I’m spending hours a day writing something, during much of the rest of the day my subconscious is engaged in it also, and everything I see—a man eating toast in a Honda at a stoplight, a woman wiping out on the ice outside Macy’s—becomes research, becomes material.

Q: Your stories are often set in unconventional locales—the Alaskan tundra; Lamu, Kenya and Liberia, West Africa; rural Montana and Idaho; Lithuania; an island in the Caribbean—not what one might expect from an Ohioan. One of your characters moves from Ohio to the East Coast to become a shipbuilder, a romantic venture that cannot be supported. Many of your characters move from one place to another that is very much unlike the first. What are your characters seeking, and what do they find? Why this emphasis on the journey, the extremes in setting?

A: Movement is a kind of narrative I’m preoccupied with. I’m magnetically drawn to stories that establish two places and string a character out between them: Huck Finn, Madame Bovary, Disgrace, The Odyssey, pretty much every A.S. Byatt story. All of my favorite stories, I think, involve some kind of duality—that’s where tension comes from, and conflict. A character is in one place but wants to be elsewhere. A character is trapped somehow, and works to free herself. So these are the kinds of stories I try to write. Storytelling itself is, maybe, the act of moving from one place to another, or leaving one place and returning to it once more, but changed somehow.